À basic definition of YARNBOMBING is found in WIKIPEDIA “a type of graffiti or street art that employs colourful displays of knitted or crocheted yarn or fibre rather than paint or chalk”(1)

A more comprehensive definition is

Yarnbombing is part of street art, part graffiti, part activism, which combines the seemingly “cute”and comforting elements of knitting and crochetin , with the revolutionary and mild civil disobedience of graffiti/”tagging”of public objects, in order to make some sort of artistic statement. (2)

This references the “cute”nature of yarn bombing but does not include the what, for many, is the most important aspect of the action. Many practitioners refer to using yarnbombing in order to feminise a space ,or an object.

(3)

It is useful to consider where yarn bombing fits in the general art world. While a definition of graffiti places many pieces in that context, the larger (and probably more thoughtful pieces) align themselves with the wrapping work of Chris to and Jean-Claude (4), and work within the Soft-Sculpture movement. (5) . Yarn bombing is often carried out by participants who have no connection to the formal art world and thus it could be considered as “outsider” art.

Yarn bombing hasbecome so ubiquitist there are books sold on AMAZON with HOW TO DO instructions. (6) This availability must inevitably lead to an increase in Yarn bombing.

The problem with Yarn bombing arises from the very ease of producing the elements that make up a piece. Knitting is not an expensive craft to learn nor is it particularly difficult. À beginner can produce a reasonable square of kniiing after a couple of lessons and a few hours practice. Obviously pattern knitting and three dimensional shaping are skills that take time and practise to master. Close investigation of Yarn bombing work shows that most of it is made of basic shapes in basic knitting techniques joined together to make a larger work.

Bright colour is often a feature of Yarn bombing work. This is usually achieved by knitting stripes in a basic unit, or combing different coloured basic units. High quality specialistvyarns are quite expensive but mass produced acrylic yarn is readily available in supermarkets. Most knitters accumulate a stock of single balls of Yarn left over from previous projects, and charity shop sell off mixed lots. These accumulations mean that multi-coloured work is easily achieved.

Knitting is a craft that can be practised within a group. The participants all work on their individual units in the same place and interact socially as they work. In a communal setting this engenders a cohesive and supportive group. Combined with the initial ease of production and relative cheapness of the materials , this makes yarn bombing an ideal activity for community groups. These can be “oneaction”groups (7)or more substantial and continuing groups.

Yarn bombing falls into two main areas. Some practioners produce forms that imitate the real world in some way. The second type works in a more abstract way, interacting more directly with the physical environment.

THIRSK Yarnbombers began in 2015 and has involved up to 300 local people. It’s work has become an important part of the local attractions (8). Their work is well documented on their Facebook page (9) and on the Thirsk Tourist Information page. (10) It is clear from the photo that the Thirsk yarnbombers have a level of skill well above the basic.

This type of Yarn bombing aims to be amusing, “cute”(11), to make you smile. H owever it is very much an individual taste as to whether the viewer enjoys these pieces or finds them horrendous kitsch.

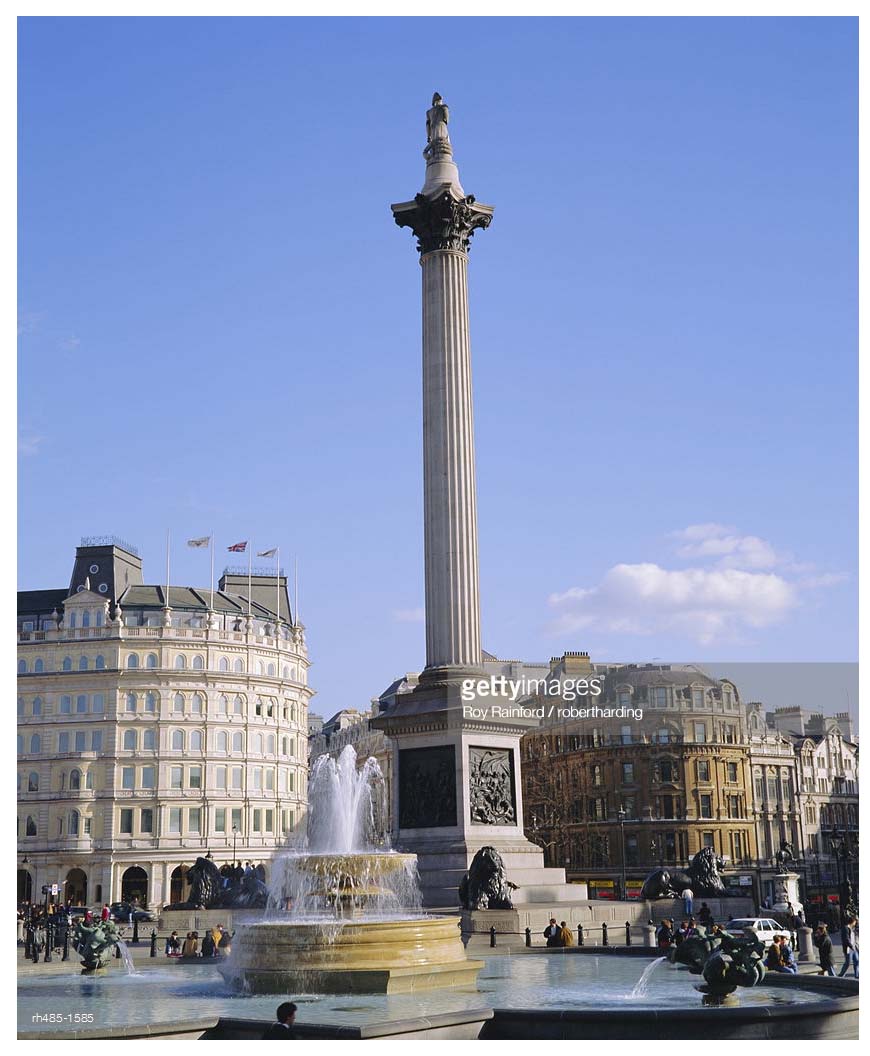

Again the abstract yarnbombers tend to work communally but their work often involves wrapping street furniture, trees and even public monuments.

(12)

(13)

It is clear from these two images that abstract Yarn bombing is not necessarily visually successful, no matter how worthy the aims of the community group involved.

Whether or not the work is visually appealing or artistically justifiable there are two further linked problems, the yarn used and the dismantling of the piece. Whether the yarn is natural (wool,cotton) or artificial (e.g. acrylic, polyester)it will fade and disintegrate. Wet weather will cause anything made in wool to sag, some yarns will shrink and where a mixture of yarns are used in time the piece will appear puckered. Sun will eventually fade the colours and aide the deterioration of the yarn.

Further there are environmental concerns

Yarn bombing has been under some scrutiny for the potential negative environmental impact that the yarn can have when placed on plant life. Yarn can restrict sap production on trees and constrict growth. (14)

Most yarns are a combination of fibres. While wool and cotton will eventually rot away, synthetic fibres will simply be around for ever adding to the pollution of the micro-climate.

It is clear that part of any yarnbombing is the dismantling of the work and the clearing away of the materials used. Chris to and Jean-Clude carefully removed all their work, even dismantling it early when it became damaged by the weather (15) They often disposed of the materials used by donating it to locals.

It is sometimes difficult for community groups who have worked long and hard on a project to realise that its temporary nature is an essential part of the project.

So what are the problems with yarnbombing. The problems are those found with any installation. Either it appeals to the viewer or it doen’t, it is well done or it isn’t, it achieves its aims or it doesn’t.

And if there is too much of it, remember that it is g raffitti when all is said and done

NOTES

(1) https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Yarn_bombing

(2) https://davidcharlesfox.com/whar-is-yarn-bombing-about-the-guerrilla-knitting-art-movement/

(3Kristina Kroemer in davidcharlesfox.com

(4) c.f. the wrapping of the Pont Neuf and te “bombed bridge”.

(5) https://www.artsy.net/gene/soft-Sculpture for a brief overview

(6) AMAZON listed8 books under the search title YARNBOMBING

(7)Groups of knitters came together to decorate their areas during the Tour de France in Yorkshire

(8)https://www.visitthirsk.org.uk/pages/yarnbombers.pho

(9) https://www.Facebook.com/tyb2016/photo

(10) http://www.visitthirsk.org.uk

(11) https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/cute defines cute as 1) attractive, usually small, and easy to like 2)informal -sexually attractive

(12) artist unknown

(13) artist unknown

(14) wikipedia/wiki/yarn_bombing

(15) After it was installed, the builders removed it 14 days later, leaving novisible trace behind . See https://en.Wikipedia./org/wiki/runing_fence

b

and in it’s totality

and in it’s totality

ii

ii  [3]

[3] [13]

[13]